Mental Health inequalities mirror wider Economic and Social inequalities.

We all know the proverb, ‘Money doesn’t buy happiness’. Whilst this sentiment (one echoed in our lockdown interviews by Lyn here and Hema here) resonates with many of us it also plays into the idea that if we are unhappy it is our own fault and not one partially or entirely created by our social and economic circumstances. This isn’t true – financial fears, stress from being unable to pay bills, working from home in a house that isn’t fit for purpose and even just being unable to afford to relax with a takeaway on Saturday are all legitimate reasons to have increased pressure on one’s mental health.

The University of British Columbia found spending money to buy free time, such as “paying others to cook or clean for you, does improve happiness, leave you feeling less stressed and generally more satisfied with life.”. Other studies have shown that happiness rises with income but only until a point, at which point it plateaus. Whilst lockdown may have created a lot of spare time for those on furlough, many people in working class jobs such as supermarket workers and bus drivers (listen to our interviews with Heather a supermarket worker here and Wayne a bus driver here) continued to work whilst risking their own health. Working from home is a privilege that those in the face to face economy are not being afforded.

White-collar workers are more likely to feel both financially and emotionally secure during the pandemic, according to the New Statesman, and furthermore “The WFH phenomemon very clearly only applies – can only apply – to white-collar workers with office jobs. Those engaged in manual labour can’t work from home, so have little choice but to keep working, or find themselves unemployed. The next great socio-economic divide, then, is the “Zoom” factor: the kinds of jobs that can be done via video chat versus those requiring a physical presence.”. This socio-economic divide is likely to cause a divide in mental health too as those who cannot work from home have more reasons to fear for their health at work and also for their employment if they cannot work. This added stress and anxiety will damage the mental health of these workers and is yet another hidden health implication of the pandemic.

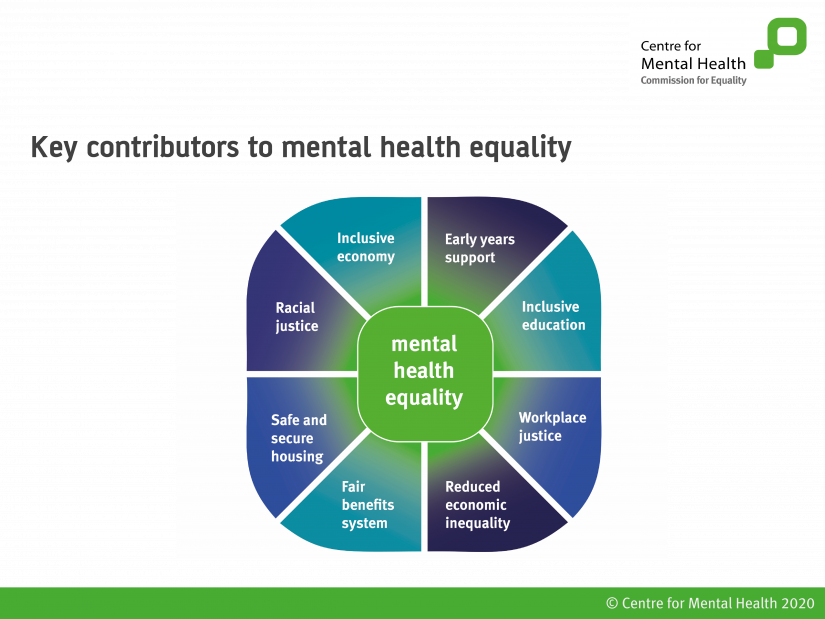

The Centre for Mental Health report Mental Health for All? found that “mental health inequalities mirror wider economic and social inequalities. Wealth and power inequalities put at risk the mental health of people experiencing poverty, racial injustice and discrimination. This creates sharp social divisions, meaning that many groups of people face two or three times the risk of mental ill health. Yet the same groups of people find it harder to get help for their mental health, and in some cases also get poorer outcomes when they do.”

How do we combat these divisions? By tackling the socio-economic divide we could in turn improve mental health. Whilst more funding for mental health services would be welcome we must also look as the cause and effect of mental health issues in our society. Putting better structures in place to stop workers fearing they won’t be able to pay the rent if they get sick could reduce stress, as could ensuring everyone is given a realistic living wage so they are not anxious about feeding themselves or paying for electricity.

Social and economic divides are linked to declining mental health and as we re-emerge from the pandemic we must ask ourselves what sort of society we want to rebuild.

Join The Conversation at The Living City on what we want Preston to look like in terms of somewhere we live, work and play.

The video below is a compilation of how our lockdown interviewees said they were feeling in lockdown and their reflections on their mental health.

You may also be interested in First Thoughts Article: The pandemic’s affect on mental health in Preston